by Kim Fabricius

1. To be human is to be contingent. This has to be said first because while ontologically it is rather obvious, existentially it is deeply problematical. One way or another, we all know that we are not necessary, that we are here without a by-your-leave, that we have been “thrown” into existence. Whether by a vicious fastball, a deceptive slider, or a graceful curve depends on your faith – or, better, your trust. But human beings do not live this knowledge of contingency. Gifts of God to the world, we live like we are God’s gift to the world. We act like we are self-caused, self-made, independent, indispensable, as though our non-existence were inconceivable. We act, in other words, like God. And in acting like God we act against God. We sin.

1. To be human is to be contingent. This has to be said first because while ontologically it is rather obvious, existentially it is deeply problematical. One way or another, we all know that we are not necessary, that we are here without a by-your-leave, that we have been “thrown” into existence. Whether by a vicious fastball, a deceptive slider, or a graceful curve depends on your faith – or, better, your trust. But human beings do not live this knowledge of contingency. Gifts of God to the world, we live like we are God’s gift to the world. We act like we are self-caused, self-made, independent, indispensable, as though our non-existence were inconceivable. We act, in other words, like God. And in acting like God we act against God. We sin.

2. To be human is to be self-contradictory. Sin is a surd, or, as Barth said, an impossible possibility. That is why we cannot fit sin into any system: it is inherently inexplicable, irrational – it doesn’t compute. To be human is also to be self-contradictory in the sense that in acting against God, we act against ourselves: we are self-destructive – we are always pushing our delete key. Indeed, left to ourselves we would destroy ourselves, irretrievably, which is not only murder but intended mass murder, for in destroying ourselves we would destroy the world. Homicide is always misdirected suicide. War always begins with a Blitzkrieg on the self. Augustine’s amor sui is in fact self-hatred.

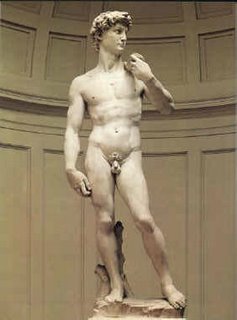

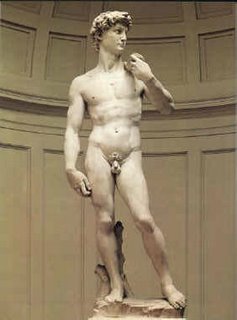

3. To be human is to be physical. We are made from earth, we return to the elements, but the human form is a wonder to behold: “the head Sublime, the heart Pathos, the genitals Beauty, the hands and feet Proportion” (Blake). Of course: this is because we are made in the image of God and God is physical – and beautiful. Process theologians are wrong when they suggest that the world is God’s body: God has his own body. God is Spirit, but “to think about the Spirit you have to think materially” (Eugene F. Rogers Jr.), you have to think body. Further, to be human is to be sexual. Desmond Tutu once said that Adam’s first word upon awakening from the surgery that issued in Eve was “Wow!” To which Eve no doubt replied, “You’re not so bad yourself!”

3. To be human is to be physical. We are made from earth, we return to the elements, but the human form is a wonder to behold: “the head Sublime, the heart Pathos, the genitals Beauty, the hands and feet Proportion” (Blake). Of course: this is because we are made in the image of God and God is physical – and beautiful. Process theologians are wrong when they suggest that the world is God’s body: God has his own body. God is Spirit, but “to think about the Spirit you have to think materially” (Eugene F. Rogers Jr.), you have to think body. Further, to be human is to be sexual. Desmond Tutu once said that Adam’s first word upon awakening from the surgery that issued in Eve was “Wow!” To which Eve no doubt replied, “You’re not so bad yourself!”

4. To be human is to be spiritual. But not, needless to say, spiritual as against physical. Unlike Greek anthropology, Christian anthropology is not dualist, it understands human beings as ensouled bodies and embodied souls. Faith itself, Luther said, “is under the left nipple.” Hence the crypto-gnosticism of any soma sema “withdrawal” spirituality. We may speak of the “inner life”, of “interiority”, but it “is neither a flight from relation, nor the quest for an impossible transparency or immediacy in relation, but that which equips us for knowing and being known humanly, taking time with the human world” (Rowan Williams). The self is not secret, it is social.

5. To be human is to be relational. Again, of course: this is because God, as Trinity, is relational. The perichoretic God makes perichoretic people. God’s being-as-communion overflows in humans’ being-in-community. Jesus was the “man for others” (Bonhoeffer); humans have no being apart from others. Humanity is co-humanity: our very identities are “exocentric” (Pannenberg). Margaret Thatcher notoriously said that there is no such thing as society; on the contrary, there is no such thing as autonomy. Here lies the bankruptcy of all social contract theory. Further, as relational, social beings, we are linguistic beings, modelled on the Deus loquens. Here lies the theological import of Wittgenstein’s observation that there is no such thing as a private language.

6. To be human is to be responsible. That is the inner meaning of the “dominion” of Genesis 1:26, which is a dominion not of domination but of stewardship, “dominion by caretaking” (Michael Welker). Yet again, of course: God the world-maker is God the care-taker. Humans properly stand over other creatures only as they stand with other creatures, showing them love, giving them space, and granting them “rights”. Humans are royally privileged, but noblesse oblige. Thus to be human is to be ecological. It is also, of course, to be political. Finally, insofar as we do as we are, we are free – for freedom, libertas, is not the freedom of “choice”, which in fact is slavery, but the freedom for service.

7. To be human is to be ludic. Humans are the animal that plays and laughs. And – yet again – of course: this is because God plays and laughs. Creation itself is play, not work. On the first Sabbath God smiled – and partied! Eight-year-old Solveig is right, against her Poppi, that “Santa Claus is very much like God”, because he is so “jolly” (in Robert Jenson’s Conversations with Poppi about God). And (in Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose) the bespectacled Franciscan William is right, against the blind Dominican Jorge, that Jesus surely laughed, because he was fully human (tellingly, Jorge objects because laughter “convulses the body” – like sex). Indeed when humans laugh they ape the angels, who, as Chesterton said, “can fly because they take themselves lightly.”

7. To be human is to be ludic. Humans are the animal that plays and laughs. And – yet again – of course: this is because God plays and laughs. Creation itself is play, not work. On the first Sabbath God smiled – and partied! Eight-year-old Solveig is right, against her Poppi, that “Santa Claus is very much like God”, because he is so “jolly” (in Robert Jenson’s Conversations with Poppi about God). And (in Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose) the bespectacled Franciscan William is right, against the blind Dominican Jorge, that Jesus surely laughed, because he was fully human (tellingly, Jorge objects because laughter “convulses the body” – like sex). Indeed when humans laugh they ape the angels, who, as Chesterton said, “can fly because they take themselves lightly.”

8. To be human is to be doxological. In Peter Shaffer’s play Equus one of the characters says that if we don’t worship, we shrink. Not to worship is spiritual desiccation. Worship is to the heart what water is to the tongue. Not that worship is for anything. Worship, in fact, is totally useless. Indeed the question “Why worship God?” is a foolish one. “We worship God because God is to be worshipped” (J. R. Neuhaus); indeed God, as Trinity, is worship. As service is the ultimate expression of our freedom before others, so worship is the ultimate expression of our freedom before God. It is also the ultimate expression of human dignity, “man well drest”, as George Herbert imaged it; indeed “God’s breath in man returning to his birth.”

9. To be human is to be Christ-like. Indeed we are not truly human, only Christ is truly human, the iconic human, the imago Dei: and God himself “is Christ-like, and in him there is no un-Christ-likeness at all” (John V. Taylor). Here is the truth in the Eastern concept of deification, better, perhaps, called Christification. We are human only as we are conformed to the imago Christi, only as we are in Christ, dead and risen in him. Thus anthropology is a corollary of Christology – and staurology: Ecce homo! Thus baptism is the sacrament of humanity, because it is the sacrament of our death and resurrection en Christo (Romans 6:1-11) – and this is no metaphor! Through baptism, we become human beings – proleptically.

10. To be human is to be glorified. Anthropology is Christology is eschatology. If God has “the future as the essence of his being” (Moltmann), so too do humans. And as “the Spirit is God’s own future that he is looking forward to” (Robert Jenson), so the Spirit is the perfecter of the human. Thus the “being” in my title is a gerund: being human is a becoming human. In trajectory towards the telos, we live by promise and hasten in hope, the heart of the human. In the end, the Father will sit us on his knee and show us what we were really like – and who we really are. “Beloved, we are God’s children now; what we will be has not yet been revealed. What we do know is this: when he is revealed, we will be like him” (I John 3:2). Glorified, we will glorify – Father, Son, and Holy Spirit – “sweetly singing to each other” (Jonathan Edwards).

And all shall be well and

All manner of things shall be well

When the tongues of flame are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.

—T. S. Eliot, “Little Gidding,” Four Quartets