Michael Pomazansky: Orthodox Dogmatic Theology

Michael Pomazansky, Orthodox Dogmatic Theology: A Concise Exposition, 3rd edition (Platina: St Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2005), 434 pp. (with thanks to the publishers for a review copy).

Michael Pomazansky, Orthodox Dogmatic Theology: A Concise Exposition, 3rd edition (Platina: St Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2005), 434 pp. (with thanks to the publishers for a review copy).

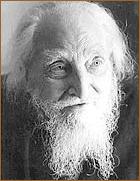

Michael Pomazansky’s Orthodox Dogmatic Theology (available now in a third edition with extensive new footnotes) has long been a significant textbook of conservative Orthodox theology. Pomazansky was born in western Russia in 1888, and he studied at the pre-revolutionary Kiev Theological Academy from 1908 to 1912. He served as a theologian and missionary in Russia and then, after the revolution, as a priest and editor in Poland and Germany. In 1949 he moved to the Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, New York, where he remained until his death in 1988 (just days before his 100th birthday!).

For Western Christians, encounters with Orthodoxy can be a bewildering experience. As Georges Florovsky once remarked, while Catholics and Protestants speak a similar language, there is fundamentally no “common universe of discourse” between East and West. This does not mean that understanding is impossible – but it explains the great difficulties involved in such dialogue, and it helps to account for the comparatively slow progress of ecumenical understanding between East and West. In Orthodox Dogmatic Theology, Pomazansky himself is more or less closed to Western influences: he refers to Catholic and Protestant ideas only where a polemical point is in order; and much of the book is concerned with implicit or explicit controversy with more liberal Orthodox theologians like Vladimir Soloviev and Sergei Bulgakov.

In Orthodox Dogmatic Theology, Pomazansky himself is more or less closed to Western influences: he refers to Catholic and Protestant ideas only where a polemical point is in order; and much of the book is concerned with implicit or explicit controversy with more liberal Orthodox theologians like Vladimir Soloviev and Sergei Bulgakov.

In spite of this, however, Pomazansky’s work provides valuable insight into the distinctiveness of Orthodox dogma in contrast to Western patterns of thought. Indeed, Pomazansky is at his best when he is engaged in critique of Catholic dogma (see for instance pp. 89-93 on the Filioque), or when he explains that an apparent similarity between Eastern and Western views is in fact masking a much deeper divergence.

His criticisms of “legal” patterns of thought in Western doctrine are especially incisive (and, to my mind, essentially correct). He rightly critiques Western doctrines which define redemption as “satisfaction of wrath,” for instance (pp. 213-15); and in an excellent chapter on sin, he criticises the Western tendency towards a “very legalistic, formal” doctrine of original sin and inherited guilt (pp. 162-69). Again, in a very fine discussion of Mariology (pp. 189-97), he notes that the Catholic dogmas of the immaculate conception and the assumption are logically derived from a misleadingly forensic doctrine of original sin.

In contrast to more progressive tendencies in modern Orthodox thought, Pomazansky’s is a highly conservative theology. Indeed, his entire conception of the theological task is one of conservation: dogmatics consists in “the confirmation in the consciousness of the faithful of the truths of the faith which have been confessed by the Church from the beginning” (p. 46), so that it is out of place to reveal “new aspects” or “new understanding[s]” of dogma (p. 47). Indeed, dogma itself cannot “develop,” since there is simply “nothing to add to the teaching of faith handed down” (p. 355). From a Protestant perspective, of course, one could easily connect such themes to a certain conception of divine eternity and immutability: “For God there is neither past nor future; there is only the present” (p. 67); “God is perfection, and every change … is unthinkable” (p. 72).

Nevertheless, even such conservative emphases give expression to the depth and beauty of theological reflection, for, in Pomazansky’s view, “theologizing is not an abstract mental exercise, … but a dwelling of one’s thought in Divine truths, a directing of the mind and heart towards God” (p. 48). And in its best moments, Pomazansky’s work is indeed characterised by a spirit of reverence and adoration – something one does not always encounter in a typical wissenschaftlich work of Protestant dogmatics! To believe in God, Pomazansky writes, means “not only to acknowledge God with the mind, but also to strive towards Him with the heart…. Christian faith is a mystical revelation in the human soul. It is broader, more powerful, closer to reality than thought” (p. 53).

Admittedly, one can find more exciting and more creative Orthodox thinkers – Lossky, Schmemann and Meyendorff, for instance; or, more recently, John Zizioulas and David Bentley Hart. But for a sober, serene and straightforward exposition of Byzantine dogma, Pomazansky’s Orthodox Dogmatic Theology remains valuable and instructive.

If the value of Pomazansky's work is its incisiveness in criticizing Western Christianity (without it would seem, entering into positive dialogue with it - I think of the counter-example of Barth and Balthasar), then it would be helpful to know which sources he relies upon for his understanding of Western Christianity.

What was his awareness of the broad European cultural work of ressourcement (Newman, Peguy, de Lubac, Blondel, Danielou, Balthasar, Ratzinger, Giussani, etc)? What is his take on the gestures of rapproachment with the East in the Second Vatican Council including the restoration of the invocation of the Holy Spirit? Since he died in 1988, he also missed seeing the Catechism of the Catholic Church (with its joining of Eastern and Western perspectives) and the construction of Redemptoris Mater Chapel.

The juridical, or legal, approach of the West has been discussed repeatedly in Communio: International Catholic Review, among other Western sources. It's a common feature of Western self-critique. So, what does Pomazansky add to this?

Hi Fred. Thanks for this comment -- I'm entirely sympathetic with what you say here.

To answer your last question: No, I certainly don't think Pomazansky adds anything new to the discussion! Rather, I think the usefulness of his book lies simply in the clear picture it gives of Orthodox dogma in distinction from Western dogma.

But as I said above, he has no interest at all in ecumenical understanding (and he seems very suspicious of any movement in this direction): he's interested solely in articulating Orthodox belief, which occasionally requires polemic against the West. But in just that way (and in spite of my own basic disagreements with the whole procedure!), I think his work does offer a genuinely helpful perspective on some of the differences between East and West.

Anyway, I certainly appreciate all your reservations: I guess I'm just trying to offer the best possible reading of his work, in spite of all the things that could be said against it.

Thanks, Ben. Actually, I think his book would be valuable for its glimpse inside the conservative Orthodox world. I've met a few of these Orthodox and they're not the easiest folks to discuss things with. But if we don't meet them on their own turf, we're just practicing an ecumenism of like-minded folk.

It also occurs to me that the Catholic Church has been wrestling with the Eastern critique for some time and I see how this book could offer some Protestant Westerners an opportunity to meet this critique directly, instead of via the Roman ressourcement.

Fred

So far this semester I've read Bouteneff, Lossky, Alfeyev, Ware and Schmemann. I wasn't happy with any of them, well Schmemann was actually quite good but I'm just not happy with the Eastern dogmatic theology. I think the biggest value was to help me appreciate my Western heritage. I found it interesting that I had never heard of this guy, but I am familiar with Bulgakov. It might have something to do with the fact that the EC prof I have is an Eastern Catholic who is involved with the East-West Ecumenical dialogues (even thought the Eastern Catholics are a bit of a thorn for that process). I enjoyed your review though.

I left my comment but bloggerr lost it. I'm not writing ity again.

How many Western theologians know about or refer to any Orthodox theologians in their books?

Western theologians expect Orthodox theologians to be familiar with their stuff, but rarely bother to familiarise themselves with Orthodox theology.

Sorry I'm not writing carefully, because blogger will probably lose it again anyway.

Hey Steve, I'm always impressed by how often I see Orthodox theologians referenced in theological works. I am doubly impressed now that I know how little use I would immediately find in Orthodox dogmatic frameworks. But where they reference it is the place I was most interested in, the sacramental life. Then again the Orthodox theologians I've been reading are far from ignorant of Protestant and Catholic theologies. I am about to hand in my final reflection paper for my Eastern studies course and in it I took the opportunity to talk about our mutual strengths and weaknesses and urge us to all humbly recognize a desire to be faithful to Christ. If we can recognize this seed of desire then it will go a long way in bridging the Orthodox and orthodox worlds.

I had and read this book several years ago. I'd have to warn you from the Orthodox side that there are reservations among Orthodox catechists and others regarding this book. The Platina Brotherhood is known as one of the outliers of Orthodoxy, as is Holy Trinity Monastery (though of course, they claim to be "true" Orthodoxy; call them schismatic if you will; they are not part of the Communion). This Pomazansky manual simply cannot be taken as representative of the wider theological tradition in Orthoodxy, despite the author's devotion and erudition. It is one perspective, based in a more rigidly dogmatic theological tradition that is quite typical of Russian Orthodoxy, and good to learn of if one keeps it in sight as part of that context. But a valid summary of the whole, it is not. This is not to say that Eastern Orthodoxy is non-dogmatic, which would be absurd. But the extent or depth of its particular approach taken in this book left a bad taste in this well-read Orthodox reader's mouth. Read it with caution. Others have mentioned Lossky, Meyendorff, Zizioulas. Those are a better beginning, the first for mystical theology, the second for interaction with particularly American religion, the third for wider philosophical discussions.

I will try again, in the hope that Blogger doesn't lose it all.

One criticism I have heard of Pomazansky's book from an Orthodox point of view is precidely that it is too Western, not so much in its content as in its style. Pomazansky takes a Western scholastic approach. This was quite common in Russian theological academies a couple of centuries ago, but there it was balanced by the monastic life.

Having said that, however, it is useful compendium of Orthodox dogmatic theology for Orthodox Christians living in the West, where general culture has been influenced more by Western theological assumptions. Pomazansky isn't concerned to present the various nuances of Western theology and compare them with Orthodoxy. He is concerned to present the core of the Orthodox dogmatic tradition, and mentions Western theology where it might, because of its general cultural influence, cause confusion about what Orthodoxy actually teaches.

One can see these general cultural assumptions in the arguments used by Western atheists in newsgroups, for example. They have a conception of God that is built up from many cultural assumptions, and most of them haven't gone into the nuances of Western theology either. Most Westenr theologians probably don't believe in the God that Western atheists disbelieve in, but that conception of God is even further from Orthodox conceptions, and there are strands in Orthodox theology that reject conceptions about God altogether (ie apophatic theology).

That said, Pomzansky's book is probably a good read for Western Christians who want to have theological discussions with Orthodox Christians. It will at least prepare them by letting them know what they can assume and what they cannot assume. All too often ecumenical discussions get bogged down on hidden presuppositions. Both Orthodox and Western theologians presuppose a lot of things that they often do not realise that their interloqutors do not presuppose. Pomazansky's book can help clear up some of those misconceptions.

Many thanks, Steve, for such a helpful comment.

I completely concur with Steve. As long as it is realized that this book is something of an introductory text, it possesses value. But it should not be considered a definitive treatment of Orthodox dogmatic theology.

I might add that I have found Pomazansky's book useful on occasions when Western Christians ask me (as some have) whether the Orthodox Church is pre-mill post-trib or post-mill pre-trib, and I have to look up those things to find what they mean and then wonder what the Orthodox response should be.

On another (earlier) occasion, when we had been discussing something else, someone told me that the view I had expressed was only to be expected because of the Orthoxod Church's amillennarian position, and I didn't even know that, or even what an amillennarian position was. Pomazansky is quite helpful in such circumstances.

I think Kevin must have unwittingly confused Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, New York, with Holy Transfiguration Monastery in Brookline, Massachusetts. The former is the chief monastic center of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia; the latter that remains in grievous and obstinate schism from the Church’s communion. Protopresbyter Michael Pomazansky served as Professor of Dogmatics at the Holy Trinity Orthodox Seminary (attached to the monastery in Jordanville) from his arrival to North America in 1949, and he remained there until his death in 1988, three days short of his 100th birthday.

Of course, when Kevin warns that "from the Orthodox side that there are reservations among Orthodox catechists and others regarding this book," he is quite correct. As others have also noted, the shape of Father Michael's dogmatic exposition is quite "scholastic" in method (if not in content); this was, however, largely the shape of Orthodox dogmatics both under the Turkokratia and within post-Petrine Imperial Russia. Needless to say, this mold necessarily inhibits some of the native verve of Orthodox dogmatics--and this should not come as a surprise to Western Christian systematic theologians, who are keenly aware of how such things as the formulation and ordering of loci can affect a system of theology. Thankfully, however, Father Michael attempts no such system, but rather only aims at an ordered exposition of traditional Orthodox dogmatic content. Here, as Kevin notes, one must keep in mind that this only is an introductory manual: the book grew out of Father Michael's lectures at Jordanville, which is an undergraduate institution.

(I must say this, however: in my experience, much of the criticism of Father Michael's book and others like it--for instance, Ioannis Karmiris' Synopsis of the Dogmatic Theology of the Orthodox Catholic Church--comes not from the considerations above, but from a wholly fastidious attitude often found in contemporary Orthodox circles, particularly of the heavily-Westernized-yet-West-condemning Parisian orbit and the fanatical/hysterical Greek peanut gallery, which regard any systematic treatment of dogmatics as--you guessed it!—a result of the "Western captivity." This is both reductionistic and irritating, and it fails to account for, among others, St John of Damascus. But I digress.)

Yes, Esteban, you are perfectly correct! I did confuse the two monasteries, for which I seek forgiveness.

Your characterization of the "French Connection" is priceless. The approach of the Parisian Russian Orthodox transplanted to America is worthy of further study, shall we say, to be diplomatic! There is much to be done.

For me now, I keep in mind the phrase of St Silouan, that I learned from Metropolitan Kallistos, "Love could not bear that." This single sentence bears the universe in its grasp. It is now my personal philosophy!

Pomazansky's Dogmatics is itself trapped in Western scholastic categories. It lacks the very foundations of Orthodox Patristic Dogmatics. Any "Dogmatics" that makes no mention of the distinction between created and uncreated and between God's essence and energy is not Orthodox dogmatics. The book has not a single mention of the word "energy".

Post a Comment