Michael Pomazansky, Orthodox Dogmatic Theology: A Concise Exposition, 3rd edition (Platina: St Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2005), 434 pp. (with thanks to the publishers for a review copy).

Michael Pomazansky, Orthodox Dogmatic Theology: A Concise Exposition, 3rd edition (Platina: St Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, 2005), 434 pp. (with thanks to the publishers for a review copy).

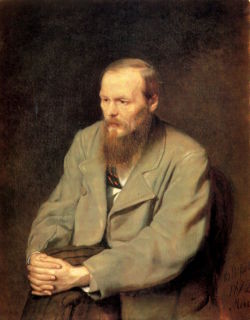

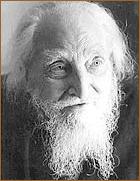

Michael Pomazansky’s Orthodox Dogmatic Theology (available now in a third edition with extensive new footnotes) has long been a significant textbook of conservative Orthodox theology. Pomazansky was born in western Russia in 1888, and he studied at the pre-revolutionary Kiev Theological Academy from 1908 to 1912. He served as a theologian and missionary in Russia and then, after the revolution, as a priest and editor in Poland and Germany. In 1949 he moved to the Holy Trinity Monastery in Jordanville, New York, where he remained until his death in 1988 (just days before his 100th birthday!).

For Western Christians, encounters with Orthodoxy can be a bewildering experience. As Georges Florovsky once remarked, while Catholics and Protestants speak a similar language, there is fundamentally no “common universe of discourse” between East and West. This does not mean that understanding is impossible – but it explains the great difficulties involved in such dialogue, and it helps to account for the comparatively slow progress of ecumenical understanding between East and West.

In Orthodox Dogmatic Theology, Pomazansky himself is more or less closed to Western influences: he refers to Catholic and Protestant ideas only where a polemical point is in order; and much of the book is concerned with implicit or explicit controversy with more liberal Orthodox theologians like Vladimir Soloviev and Sergei Bulgakov.

In Orthodox Dogmatic Theology, Pomazansky himself is more or less closed to Western influences: he refers to Catholic and Protestant ideas only where a polemical point is in order; and much of the book is concerned with implicit or explicit controversy with more liberal Orthodox theologians like Vladimir Soloviev and Sergei Bulgakov.

In spite of this, however, Pomazansky’s work provides valuable insight into the distinctiveness of Orthodox dogma in contrast to Western patterns of thought. Indeed, Pomazansky is at his best when he is engaged in critique of Catholic dogma (see for instance pp. 89-93 on the Filioque), or when he explains that an apparent similarity between Eastern and Western views is in fact masking a much deeper divergence.

His criticisms of “legal” patterns of thought in Western doctrine are especially incisive (and, to my mind, essentially correct). He rightly critiques Western doctrines which define redemption as “satisfaction of wrath,” for instance (pp. 213-15); and in an excellent chapter on sin, he criticises the Western tendency towards a “very legalistic, formal” doctrine of original sin and inherited guilt (pp. 162-69). Again, in a very fine discussion of Mariology (pp. 189-97), he notes that the Catholic dogmas of the immaculate conception and the assumption are logically derived from a misleadingly forensic doctrine of original sin.

In contrast to more progressive tendencies in modern Orthodox thought, Pomazansky’s is a highly conservative theology. Indeed, his entire conception of the theological task is one of conservation: dogmatics consists in “the confirmation in the consciousness of the faithful of the truths of the faith which have been confessed by the Church from the beginning” (p. 46), so that it is out of place to reveal “new aspects” or “new understanding[s]” of dogma (p. 47). Indeed, dogma itself cannot “develop,” since there is simply “nothing to add to the teaching of faith handed down” (p. 355). From a Protestant perspective, of course, one could easily connect such themes to a certain conception of divine eternity and immutability: “For God there is neither past nor future; there is only the present” (p. 67); “God is perfection, and every change … is unthinkable” (p. 72).

Nevertheless, even such conservative emphases give expression to the depth and beauty of theological reflection, for, in Pomazansky’s view, “theologizing is not an abstract mental exercise, … but a dwelling of one’s thought in Divine truths, a directing of the mind and heart towards God” (p. 48). And in its best moments, Pomazansky’s work is indeed characterised by a spirit of reverence and adoration – something one does not always encounter in a typical wissenschaftlich work of Protestant dogmatics! To believe in God, Pomazansky writes, means “not only to acknowledge God with the mind, but also to strive towards Him with the heart…. Christian faith is a mystical revelation in the human soul. It is broader, more powerful, closer to reality than thought” (p. 53).

Admittedly, one can find more exciting and more creative Orthodox thinkers – Lossky, Schmemann and Meyendorff, for instance; or, more recently, John Zizioulas and David Bentley Hart. But for a sober, serene and straightforward exposition of Byzantine dogma, Pomazansky’s Orthodox Dogmatic Theology remains valuable and instructive.