by Kim Fabricius

1. The more literal, the less literary a person is likely to be – and vice versa. A survey of the reading habits of fundamentalists would be an interesting exercise. I suspect that they would score low on reading classical and Booker/Pulitzer prize fiction – and even lower on poetry. I wonder what they would make of William Empson’s seminal study Seven Types of Ambiguity. To plagiarise Paul, the literal crucifies, the literary resurrects: meaning walks through closed doors. “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant” (Emily Dickinson).

1. The more literal, the less literary a person is likely to be – and vice versa. A survey of the reading habits of fundamentalists would be an interesting exercise. I suspect that they would score low on reading classical and Booker/Pulitzer prize fiction – and even lower on poetry. I wonder what they would make of William Empson’s seminal study Seven Types of Ambiguity. To plagiarise Paul, the literal crucifies, the literary resurrects: meaning walks through closed doors. “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant” (Emily Dickinson).

2. It is an interesting fact that fundamentalism is predominantly a Protestant phenomenon, a reductio ad absurdum of the Reformers’ emphasis on the literal meaning of scripture to the exclusion of the medieval “fourfold vision” (Blake). Is there a lurking fear here of a connection between polyvalence and polytheism? How ironic that, on the contrary, an insistence on a single, solid, certain meaning – i.e. semantic closure – is indicative of idolatry. The burning bush is the horticulture of divine deconstruction, and the golden calf is bull.

3. Another interesting fact: the rise of Protestant literalism went hand in hand with the desacralisation of nature, which – the good news – entailed the rise of the natural sciences, but which also – the bad news – issued in the evacuation of God from the material world, soon followed the absence of God from the world of culture. Modernist atheism itself is the spawn of biblical literalism. And when belief did a bunk, it was the priesthood of poets that helped keep the rumour of transcendence alive.

4. So another connection: the “disenchantment” of nature (Weber) and the impoverishment of the imagination. Chesterton observed a “combination between logical completeness and spiritual contraction.” And he said: “Poetry is sane because it floats easily in an infinite sea; reason seeks to cross the infinite sea, and so makes it finite.” There is also the spiritual contraction, the failure of imagination, of legalism and moralism. Hence R. S. Thomas’ description of Welsh Nonconformity as “the adroit castrator of art.”

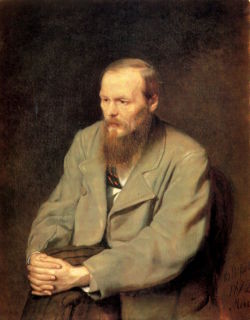

5. There has been much discussion at F&T about the nature of theology as a science. Of course – this is a Barthian blog! But Barth himself was a master of stirring rhetoric and stunning imagery. And, of course, there was his passion for Mozart, and his admiration for Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov and Melville’s Moby-Dick. Barth wasn’t so hot on the visual arts – a Protestant prejudice! – but the Church Dogmatics is a cathedral, stained glass windows and all. In short, if theology is a science, it is also an art.

5. There has been much discussion at F&T about the nature of theology as a science. Of course – this is a Barthian blog! But Barth himself was a master of stirring rhetoric and stunning imagery. And, of course, there was his passion for Mozart, and his admiration for Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov and Melville’s Moby-Dick. Barth wasn’t so hot on the visual arts – a Protestant prejudice! – but the Church Dogmatics is a cathedral, stained glass windows and all. In short, if theology is a science, it is also an art.

6. Which should not be the least bit surprising. After all, God-talk is impossible without the deployment of analogy and metaphor, and the Bible is incomprehensible apart from a narrative hermeneutics. Is it not therefore a scandal that, until recent times, theology has been in thrall to an ontological and epistemological captivity – and inevitable that it would take a Catholic, Hans Urs von Balthasar, to write a theological aesthetics and dramatics? Is not faith itself an imaginative perception of reality?

7. Theological ethics – another test case. Fundamentalist ethics are rule-based, and the answers to moral problems are found, decontextualised, at the back of the (good) book. Jesus’ preferred method of ethical instruction, however, is the parable, “subversive speech” (William R. Herzog II). Indeed Richard B. Hays argues that a “symbolic world as context for moral discernment” is fundamental to the entire New Testament. “The kingdom of God is like this.” Enter the story, work it out – then act it out!

7. Theological ethics – another test case. Fundamentalist ethics are rule-based, and the answers to moral problems are found, decontextualised, at the back of the (good) book. Jesus’ preferred method of ethical instruction, however, is the parable, “subversive speech” (William R. Herzog II). Indeed Richard B. Hays argues that a “symbolic world as context for moral discernment” is fundamental to the entire New Testament. “The kingdom of God is like this.” Enter the story, work it out – then act it out!

8. Follow the trajectory to virtue ethics. The accent is on agency and action, dispositions and desire, time and telos. Rules are not excluded, but they function heuristically, as “perspicuous descriptive summaries of good judgments” (Martha Nussbaum), to inculcate habits appropriate to the development of Christ-like character. Moral theology works best when it tells the stories of the saints. Virtue ethics is narrative ethics, where the script is unfinished and improvisation is essential. The Christian life is jazz.

9. One of the great filmic send-ups of biblical literalism: the opening scene of Monty Python’s Life of Brian. The camera pans to Jesus preaching the Sermon on the Mount, and then to a group at a distance where our Lord’s voice doesn’t quite carry. “Blessed are the cheese makers,” one character hears. “What’s so special about the cheese makers?” asks a woman. “Obviously it is not to be taken literally,” her husband replies; “it refers to any manufacturer of dairy products.”

10. Moral: a cultureless theology is an ecclesiastical disaster – and a “two culture” (C.P. Snow) theology is not much better. If we are ignorant of science we lapse into Idiocy 101-102: Creationism; or Imbecility 201-202: Intelligent Design. But if we are ignorant of literature, mere ignorance becomes downright dangerous – witness the nonsensical interpretations of biblical apocalypse by the religious right and its pernicious influence on American foreign policy in the Middle East. If pastors should be community theologians, community theologians should be writers-in-residence, exercising what Yoder called “word-care,” and teaching their folk how to read.

More details about the Vatican’s recent statement on faith and science can be found

More details about the Vatican’s recent statement on faith and science can be found