Ten propositions on being human

by Kim Fabricius 1. To be human is to be contingent. This has to be said first because while ontologically it is rather obvious, existentially it is deeply problematical. One way or another, we all know that we are not necessary, that we are here without a by-your-leave, that we have been “thrown” into existence. Whether by a vicious fastball, a deceptive slider, or a graceful curve depends on your faith – or, better, your trust. But human beings do not live this knowledge of contingency. Gifts of God to the world, we live like we are God’s gift to the world. We act like we are self-caused, self-made, independent, indispensable, as though our non-existence were inconceivable. We act, in other words, like God. And in acting like God we act against God. We sin.

1. To be human is to be contingent. This has to be said first because while ontologically it is rather obvious, existentially it is deeply problematical. One way or another, we all know that we are not necessary, that we are here without a by-your-leave, that we have been “thrown” into existence. Whether by a vicious fastball, a deceptive slider, or a graceful curve depends on your faith – or, better, your trust. But human beings do not live this knowledge of contingency. Gifts of God to the world, we live like we are God’s gift to the world. We act like we are self-caused, self-made, independent, indispensable, as though our non-existence were inconceivable. We act, in other words, like God. And in acting like God we act against God. We sin.

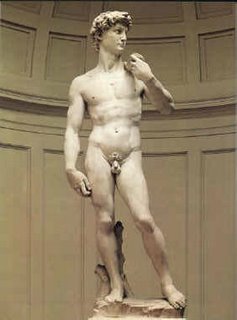

2. To be human is to be self-contradictory. Sin is a surd, or, as Barth said, an impossible possibility. That is why we cannot fit sin into any system: it is inherently inexplicable, irrational – it doesn’t compute. To be human is also to be self-contradictory in the sense that in acting against God, we act against ourselves: we are self-destructive – we are always pushing our delete key. Indeed, left to ourselves we would destroy ourselves, irretrievably, which is not only murder but intended mass murder, for in destroying ourselves we would destroy the world. Homicide is always misdirected suicide. War always begins with a Blitzkrieg on the self. Augustine’s amor sui is in fact self-hatred. 3. To be human is to be physical. We are made from earth, we return to the elements, but the human form is a wonder to behold: “the head Sublime, the heart Pathos, the genitals Beauty, the hands and feet Proportion” (Blake). Of course: this is because we are made in the image of God and God is physical – and beautiful. Process theologians are wrong when they suggest that the world is God’s body: God has his own body. God is Spirit, but “to think about the Spirit you have to think materially” (Eugene F. Rogers Jr.), you have to think body. Further, to be human is to be sexual. Desmond Tutu once said that Adam’s first word upon awakening from the surgery that issued in Eve was “Wow!” To which Eve no doubt replied, “You’re not so bad yourself!”

3. To be human is to be physical. We are made from earth, we return to the elements, but the human form is a wonder to behold: “the head Sublime, the heart Pathos, the genitals Beauty, the hands and feet Proportion” (Blake). Of course: this is because we are made in the image of God and God is physical – and beautiful. Process theologians are wrong when they suggest that the world is God’s body: God has his own body. God is Spirit, but “to think about the Spirit you have to think materially” (Eugene F. Rogers Jr.), you have to think body. Further, to be human is to be sexual. Desmond Tutu once said that Adam’s first word upon awakening from the surgery that issued in Eve was “Wow!” To which Eve no doubt replied, “You’re not so bad yourself!”

4. To be human is to be spiritual. But not, needless to say, spiritual as against physical. Unlike Greek anthropology, Christian anthropology is not dualist, it understands human beings as ensouled bodies and embodied souls. Faith itself, Luther said, “is under the left nipple.” Hence the crypto-gnosticism of any soma sema “withdrawal” spirituality. We may speak of the “inner life”, of “interiority”, but it “is neither a flight from relation, nor the quest for an impossible transparency or immediacy in relation, but that which equips us for knowing and being known humanly, taking time with the human world” (Rowan Williams). The self is not secret, it is social.

5. To be human is to be relational. Again, of course: this is because God, as Trinity, is relational. The perichoretic God makes perichoretic people. God’s being-as-communion overflows in humans’ being-in-community. Jesus was the “man for others” (Bonhoeffer); humans have no being apart from others. Humanity is co-humanity: our very identities are “exocentric” (Pannenberg). Margaret Thatcher notoriously said that there is no such thing as society; on the contrary, there is no such thing as autonomy. Here lies the bankruptcy of all social contract theory. Further, as relational, social beings, we are linguistic beings, modelled on the Deus loquens. Here lies the theological import of Wittgenstein’s observation that there is no such thing as a private language.

6. To be human is to be responsible. That is the inner meaning of the “dominion” of Genesis 1:26, which is a dominion not of domination but of stewardship, “dominion by caretaking” (Michael Welker). Yet again, of course: God the world-maker is God the care-taker. Humans properly stand over other creatures only as they stand with other creatures, showing them love, giving them space, and granting them “rights”. Humans are royally privileged, but noblesse oblige. Thus to be human is to be ecological. It is also, of course, to be political. Finally, insofar as we do as we are, we are free – for freedom, libertas, is not the freedom of “choice”, which in fact is slavery, but the freedom for service. 7. To be human is to be ludic. Humans are the animal that plays and laughs. And – yet again – of course: this is because God plays and laughs. Creation itself is play, not work. On the first Sabbath God smiled – and partied! Eight-year-old Solveig is right, against her Poppi, that “Santa Claus is very much like God”, because he is so “jolly” (in Robert Jenson’s Conversations with Poppi about God). And (in Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose) the bespectacled Franciscan William is right, against the blind Dominican Jorge, that Jesus surely laughed, because he was fully human (tellingly, Jorge objects because laughter “convulses the body” – like sex). Indeed when humans laugh they ape the angels, who, as Chesterton said, “can fly because they take themselves lightly.”

7. To be human is to be ludic. Humans are the animal that plays and laughs. And – yet again – of course: this is because God plays and laughs. Creation itself is play, not work. On the first Sabbath God smiled – and partied! Eight-year-old Solveig is right, against her Poppi, that “Santa Claus is very much like God”, because he is so “jolly” (in Robert Jenson’s Conversations with Poppi about God). And (in Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose) the bespectacled Franciscan William is right, against the blind Dominican Jorge, that Jesus surely laughed, because he was fully human (tellingly, Jorge objects because laughter “convulses the body” – like sex). Indeed when humans laugh they ape the angels, who, as Chesterton said, “can fly because they take themselves lightly.”

8. To be human is to be doxological. In Peter Shaffer’s play Equus one of the characters says that if we don’t worship, we shrink. Not to worship is spiritual desiccation. Worship is to the heart what water is to the tongue. Not that worship is for anything. Worship, in fact, is totally useless. Indeed the question “Why worship God?” is a foolish one. “We worship God because God is to be worshipped” (J. R. Neuhaus); indeed God, as Trinity, is worship. As service is the ultimate expression of our freedom before others, so worship is the ultimate expression of our freedom before God. It is also the ultimate expression of human dignity, “man well drest”, as George Herbert imaged it; indeed “God’s breath in man returning to his birth.”

9. To be human is to be Christ-like. Indeed we are not truly human, only Christ is truly human, the iconic human, the imago Dei: and God himself “is Christ-like, and in him there is no un-Christ-likeness at all” (John V. Taylor). Here is the truth in the Eastern concept of deification, better, perhaps, called Christification. We are human only as we are conformed to the imago Christi, only as we are in Christ, dead and risen in him. Thus anthropology is a corollary of Christology – and staurology: Ecce homo! Thus baptism is the sacrament of humanity, because it is the sacrament of our death and resurrection en Christo (Romans 6:1-11) – and this is no metaphor! Through baptism, we become human beings – proleptically.

10. To be human is to be glorified. Anthropology is Christology is eschatology. If God has “the future as the essence of his being” (Moltmann), so too do humans. And as “the Spirit is God’s own future that he is looking forward to” (Robert Jenson), so the Spirit is the perfecter of the human. Thus the “being” in my title is a gerund: being human is a becoming human. In trajectory towards the telos, we live by promise and hasten in hope, the heart of the human. In the end, the Father will sit us on his knee and show us what we were really like – and who we really are. “Beloved, we are God’s children now; what we will be has not yet been revealed. What we do know is this: when he is revealed, we will be like him” (I John 3:2). Glorified, we will glorify – Father, Son, and Holy Spirit – “sweetly singing to each other” (Jonathan Edwards).

And all shall be well and

All manner of things shall be well

When the tongues of flame are in-folded

Into the crowned knot of fire

And the fire and the rose are one.

—T. S. Eliot, “Little Gidding,” Four Quartets

Kim, You've waxed poetic here. It's marvelous. Only change I might make is putting point 8 up toward the top. I sympathize very much with Schmemman and his understanding of us as Homo Adorans. A characteristic, which is surely more important than that we laugh, or are physical, but perhaps you have not arranged them in order of importance. Even so, I think our function of worship deserves to be highlighted especially.

I'm interested in the idea that 'God is physical' and 'has his own body'. Does that mean that Christianity is compatible with some form of materialism or naturalism? This might be an interesting way to approach the relationship between Theology and Science. If God is physical, then the natural/supernatural distinction is meaningless and Theology is plainly a science, potentially able to have fruitful interaction with the other sciences.

What's the source of the Eugene Rogers quote you mentioned?

Wise words from Desmond Tutu! The human beings are sexual seems to create a stage for an endless struggle towards faithfulness.

Hi Miner.

Thanks for being the first to pick up on my slight change of style on this one. It is less discursive, more aphoristic, suggestive - or "poetic" as you too kindly put it - than some of my other 10 Ps. I mentioned it to Ben as a slight worry as to how readers would react. As for the placement of the homo adorans, think of it as past of the building crescendo of the last three points.

And Jonathan: By all mean take my suggestion about the corpus Dei and run with it. I clearly mean to set it within the context of the incarnation - and resurrection - of Christ. The Rogers quote comes from the fine After the Spirit: A Constructive Pneumatology from Resources outside the Modern West (2005), p. 56, in a chapter entitled "Where the Spirit Rests: Matter and Narrative". There Rogers talks about the social sciences, suggesting that "The clue to recovery of a robust Spirit-talk runs through and not around the social sciences", indeed that "Any theology that rejects the social sciences is anti-incarnational."

And Yzerfontein: Glad you like the Tutu quote. I heard it in a sermon the little big man gave at a huge gathering of Welsh Christians around twenty years ago, as apartheid was crumbling. Tutu rocks.

Thanks Kim -- brilliant as always! Any ideas about the implications of all this for the ethics of same-sex relationships?

Thank you, Anonymous. As for your question, put it like this: on Proposition 3, substitute the proverbial "Steve" for "Eve" (minus the rib) and that will give you some idea of where I stand on the matter. And I know Tutu himself would agree.

I have been very outspoken on the issue of human sexuality in my own church, and tarnished my reputation as a true blue Barthian. But then Barth's gender anthropology is one of his weakest links - and I like to think he would have changed his mind on the matter! But notwithstanding it being an important issue for the church - even if one thinks it is theologically marginal, the fact is that people are being excluded and oppressed - I'd rather not go into it on this particular post, the brief of which is larger. I hope that's okay.

Great post, Kim. I am not so sure about #9. From my reading of Scripture, Christlikeness is not an automatic feature of humanity, but is a result of grace, a gift of the Spirit and a goal of Christian discipleship.

'1. To be human is to be contingent. '

As Jesus was fully human, he was contingent.

How then could he also be God, who is a necesary being?

Kim - I like the new style.

Once again, this is a great summary of so many things and is provocative to boot. Here a few critical thoughts, though within a deep appreciation of your work here.

Does the Spirit have a body too? If so, how does your suggestion of corpus Dei differ from a Mormon tri(poly)theism? (and is God's invisibility (1 Tim 1.17, 6.16; Col 1.15) merely provisional? Or is the beatific vision to be understood straightforwardly without further comment?)

On #5 - I wonder whether we are linguistic less because we are like God and more because we are the hearers of God. The church is the creature of the divine Word, indeed, all creation gains its being from hearing and obeying the summons to be. And personally, we only ever speak once spoken to. This is one of the fundamental differences between God and humanity: God speaks, humanity listens; God initiates, humanity responds; God is active, humanity passive. Of course the reverse occurs in each case, but only within a conversation graciously initiated by God.

Is our contingency (#1) necessarily problematical? Or only contingently problematical? Unless the latter, then fallenness is equated with finitude. Cue recommendation for the James K. A. Smith book that Ben recently read.

Anthropology is a corollary of Christology - and staurology. Yes, but also of anastasiology! The crucifixion was not God's final word on either his Son or humanity.

Thanks again for this post.

Love the Chesterton quote.

Michael: I agree. Another way of putting your point, perhaps, is that we are children by adoption. But, further, even insofar as we are already in Christ by baptism - and faith -we are also on the way to being in him. The tension between the already and the not-yet in Romans 6 is clear. And there are a whole host of ways of expressing the tension doctrinally.

That was another thing I worried about - not being specific enough about the indicative and future (perfect) - and also (to anticipate Byron) between the human as created, fallen, redeemed, and glorified. That's one of the reasons I adopted the more "poetic" mode - not only to avoid long explanations but above all to allow for ambiguity and tension between the tenses. My statement in #10 about "being" being a "gerund" is crucial here, but is anticipaed in #9's "proleptically".

Stephen: Contingency isn't the half of it! How could God, who is a necessary being, suffer? The answer begins by reversing the question: How could God, who suffers (in Christ), be a necessary being? It ends in an inextricably combined thelogia crucis and theologia trinitatis.

And Byron: Always good and searching questions from Byron - which I take to be a compliment!

Does the Spirit have a body? Certainly not in the Mormon sense. But a straightforward "No" won't do either. To be honest, I've only begun scratching at the surface of this one. But if we can , must, apply words like contingency and suffering, and even death, to God, then thinking about the divine and the somatic surely needs some teasing out. And, of course, what we mean by the somatic will have to go under review. And it is not only Christian anthropology that suggests this avenue of exploration but Christology and ecclesiology. To wit: that the church is the "body" of Christ is no "mere" metaphor.

About the human as the linguistic, a Wittgensteinian counter-question: is not hearing as bound up in linguisticality as speaking? But what you say is right. Faith, after all, comes from hearing, not gobbing (which is why God gave us two ears but one mouth!). Which is also why the only an ecclesia audiens is worthy of being an ecclesia docens.

Re. contingency, see above. Or the even shorter answer: John 1:14.

And, yes, of course, a theologia - and anthropologia - crucis absolutely requires an anastasialogy.

Sory to go on, but you guys will make sharp observations which I feel obligated to honour with some kind of sketch response.

Kim, your series of propositions have always been provocative. They always demand explanation, discussion, debate, elaboration, qualification. But this series more than most. I sense at least an article, perhaps more, on theological anthropology from you. There is no way to boil down what you want to say to provocative propositions without great distortion.

But, as usual, you have those of us who read you wrestling with real meat of theology--nothing trivial, nothing shallow. That's quite a gift.

Thanks Kim. Very interesting.

Thanks for your responses, Kim. I wish I had a bit more time to write something now, but I don't. I'll have to rejoin the conversation in a day or two! Thanks for keeping us all thinking.

Michael, "Great post, Kim. I am not so sure about #9. From my reading of Scripture, Christlikeness is not an automatic feature of humanity, but is a result of grace, a gift of the Spirit and a goal of Christian discipleship."

Well, to be fully human, to reach our goal, our happiness, we must become Christ-like. We are created in the imqage of God, and in the orthodox (and catholic) tradition there is a distinction between image and likeness. We are created in the image, but created to become like God, to bedome Christ-like. So to not be Christ-like is thus to not achieve our goal, and thus not be fully human.

Kim: Superb! There is so much to ponder, discuss, repeat, and proclaim -- so much to appreciate. Thanks for this.

Byron stole the words right out of my mouth regarding the passivity of the human person coram deo: God speaks and we listen; we love because God first loved us.

I am intrigued by the emphasis on the physicality of God, but I wonder if there is a bit of modalism here, in reducing the being of God to the being of the incarnate Jesus. Of course, I trust your theological instincts more than just about anyone, but I am hesitant to go along with you on this point. Why does God have a body -- as opposed to Jesus having a body? It seems like you might be reading the imago Dei backwards, so that because Jesus is the image of God, God is then also embodied. But is not a body a feature of being created? How does an uncreated Spirit have a body?

Regarding the Rogers quote, to understand spirit in material terms is not the same as understanding spirit in the form of a body. That said, I am uncomfortable with the Rogers quote, since there is no context given for his statement. Why must we think of the Spirit in material terms? I am not disputing this point (yet), but it is not self-evident, unless he is simply clarifying the point that in speaking of God we must use anthropomorphisms -- but this has to do with human talk about God, not with the being of God.

I am also uncomfortable with the blurring of the ontological divide between God and humanity. Since having a body is a feature of being created, it seems suspect to apply this to God. And the quote from Rogers would make more sense if we were operating with a kind of panentheism, in which the world is part of God.

I know that you are only thinking christologically, and in that I can only register my wholehearted agreement. In fact, what stood out so beautifully in these propositions was precisely your steadfast emphasis upon the self-revelation of God in Jesus Christ. This was refreshing and invigorating.

I only object to one of your statements (and the theology behind it) in #5 on relational being. I do not dispute the proposition itself, only the social trinitarianism undergirding your point. I myself appreciate Zizioulas and Gunton very much, but I back away when the ontological divide between God and humanity is blurred, as in: "The perichoretic God makes perichoretic people." I would want to stress very strongly that "perichoresis" is a term applicable to the Trinity alone. Gunton is especially guilty of this, and he ends up making the word "perichoresis" synonymous with relationality. I agree with everything else you write in this section; only this line gives me pause.

I greatly appreciate these lucid, profound, and stimulating set of theses. You have my deepest respect, and I hope my thoughts are an occasion for further dialogue. Thank you for writing such a rich set of theses capable of inspiring careful theological thought on such important subjects.

I will definitely post a link to this latest installment in your series!

If I stole David's words - he stole mine. I was just writing a post about modalism, imago Dei and the distinction between creator and creature and came back here to check something, only to find my points already made! Oh well, I'll make it a shorter post and link here anyway.

Two questions...

David: I assume you do not take the language of indwelling in John 17 to be univocal?

Kim: re Barth's gender anthropology - it is interesting that in CD IV/1, 202 he links male-female asymmetrical relations to asymmetrical intra-trinitarian relations, and uses the equality affirmed by homoousia in the latter to correct any misconception of inequality in the former. I'm curious - do you think that the Son is eternally obedient to the Father or was this another Barth mistake?

Hi David.

Wow! Thanks for that! I realise that with Proposition 3 I led with my chin and fully deserve the graceful punch you (and Byron) have thrown. It is my most suggestive proposition - or, more self-critically put, the one least thought out. So thanks for doing some of the thinking for me. And very good thinking (as always) it is.

Certainly if we are going to talk sensibly about God having a body it will be a Christological discussion. That will have to be nuanced enough without bringing pneumatology into it, so perhaps I should have omitted the Rogers quote. What I'm trying to tease out is that if we say (as we must) that as Jesus suffered and died, therefore suffering and death must be predicated of God in some way, then as Jesus suffered and died in the body, do we not also have to speak of God somatically in some way? Surely of God the Son - I hear what you are saying loud and clear about modalism - but nevertheless of God the Son?

Interestingly, I have just returned to Swansea from a meeting in Cardiff. On the way, I stopped for a fix - of caffeine. And while sipping my cappuccino I continued reading Conversations with Poppi about God:

Solveig (Robert Jenson's granddaughter): . . . But Jesus still has his own body. He is not God's body.

Poppi (Jenson himself): Jesus is a body. Right. So in that sense, God does have a body.

S: Of course he has a body. He has that body. . .

But if it is true, that - economically - God has "that body", does God not also have that body immanently in some way?

No doubt having - being - a body is "a feature of being created". But, again, so is suffering and death - yet we still predicate them of God. So, yes, the question is well put: "How does an uncreated Spirit have a body?" How? You and I - as faithful Barthians - know how crucial it is to re-define conventional words in the wake of revelation. Why not the word "body" too?

On the word "perichoretic", I respect the good Calvinist intent in your hesitation in using it. And I wouldn't go to the stake for insisting on its usage. But I'm more or less with Colin on this one.

And Byron: Thanks for coming back (just as you promised!) My short answer to your question is that Barth was right that "the Son is eternally obedient to the Father." But I think it is to pull a fast one to justify any human obedience to another human - let alone a woman's to a man - by moving directly from trinitarian doctrine to anthropology. Perhaps I have been guilty of that particular theological solecism myself in my Propositions - and of the reverse! (particularly with Proposition 3 itself).

Theologising is always walking a tightrope: we need friends to keep us on it - and to keep us going. Thanks - everyone - for your help and your encouragement.

Oh, David - I forgot to add: I trust you appreciated the "the fire and the rose" conclusion to my 10 Ps. :)

Some fantastic points being bandied about here, if I may chime in...

I don't care for the usual description of God as pure spirit precisely because people mistakenly use that word to mean "disembodied". I think that Kim is right to say that God must be embodied though of course that does not mean that God is flesh and blood in the normal sense. The analogy is the reverse we are embodied only analagously to God. Spirit and Body are not in opposition. Just as we speak of heavenly bodies or bodies of water - what we mean has a more poetic thrust, which I think is essentially that God is not the opposite of substance or the opposite of defined boundaries. In some way God is capable of being "local" and "physical" which is embodied.

I definitely see how the idea of God having a body does lead very easily however into childish ideas of God as an old man with a long beard sitting on a golden throne. These are mere anthropomorphisms of God.

Kim,

I cannot believe I forgot to mention the "fire and the rose" ending! Indeed, I loved it! Thanks for including a selection from my favorite poem.

I really have nothing with which to disagree. I think Jüngel helps tease out the implications of thinking the human Jesus together with the being of God. As he writes in God's Being Is in Becoming, "the man Jesus is in the beginning with God" (96; Webster's translation). What does it mean, then, to say that the humanity of Jesus is part of God's being ad intra? This is a really perplexing part of Barth's rigorous thinking through of the doctrine of election.

I agree that we cannot divorce the human and divine natures -- i.e., we must not avoid modalism and fall into Nestorianism. But I still feel uncomfortable with then making the leap to: God has a body. But you are right that we have to allow God to redefine the terms when applied to God and not to creatures. (Enter: the doctrine of analogy.) :)

Thanks Kim for clarifying your thoughts on 'body'. Very helpful.

As for obedience (human and divine) I also agree that moving directly from immanent trinitarian life to human ethics is problematic (indeed, this is the very criticism of perichoresis (as used by e.g. Gunton) often put forward). Australian Anglicans have been having this debate recently and the position you adopt manages to sit on both sides of the fence!

On a broader note, this post inspired me to speak up at a recent sermon planning meeting and now I've scored a five week series on anthropology. Any suggestions on how to structure it?

I see absolutely no value in posting lists of unargued opinions. Are you inviting me to assent to these propositions or are you inviting me to tell you why they are wrong? I'll assume its the latter.

First things first:

Is this list supposed to be an exhaustive list of the essential properties of human nature? In other words, do these ten characteristics jointly define what it means to be human? If so, what ever happened to rationality?

Moreover, if you claim that what it means to be human is to be spiritual and physical at the same time, then you owe us an account of how this is possible. First clarify the terms being used. For something to be physical is for it to be composed of atoms, particles, and so forth. For something to be spiritual then implies that it isn't physical, by definition.

Now there are lots of entities we would want to affirm exist non-physically, such as numbers, etc. But are these theoretical entities spiritual entities? If so, how is the human person spiritual in this way. If this is not the sense you wish to give to 'spiritual', then please explain how a being can be spiritual and physical at the same time.

Perhaps, given your predilection for Heidegger, you will say that it our 'Mitsein' that makes us spiritual. Surely relations among human beings are not themselves physical entitites, so perhaps it is in virtue of these relations that our being is spiritual. After all, you say, "humans have no being apart from others."

But this is self-evidently false. Even if I were shipwrecked on an island by myself and I had no relation to anyone else in the rest of the world, I would still be a human being.

Thanks for this, Shane.

Just one quick point -- you say: "For something to be spiritual then implies that it isn't physical, by definition." Actually, that's not at all the way Christian discourse uses the term "spiritual". The way Paul uses the word "spiritual" in the NT is much more to the point: for Paul, the contrast between "spirit" (pneuma) and "body" (soma) is not a contrast of the non-physical and the physical, but rather of that which is oriented towards God and that which is not.

In other words, the human person is meant to be fully "physical", and precisely in this physicality to be fully "spiritual"!

Ben,

According to the BDAG pneuma has several meanings, three of which are especially relevant to this discussion:

"2. that which animates or gives life to the body, breath, (life-)spirit . . . 1 Pt 3:18f (some mss. read pneumati instead of pneumasin in vs. 19, evidently in ref. to the manner of Jesus’ movement; pneuma is that part of Christ which, in contrast to sarx, did not pass away in death, but survived as an individual entity after death; . . . . Likew. the contrast kata sarka . . . kata pneuma Ro 1:3f. Cp. 1 Ti 3:16."

"3. a part of human personality, spirit . . . a. when used with sarx, the flesh, it denotes the immaterial part 2 Cor 7:1; Col 2:5"

"4. an independent noncorporeal being, in contrast to a being that can be perceived by the physical senses, spirit . . . "

There is a 'physical' sense to pneuma too, since it can be translated "breath" as well. This seems to be an older meaning, however, which the NT gives a metaphorical sense to point to the nonphysical part of the person which animates the body. this is precisely what aristotle and the scholastics mean by calling the immaterial human soul the substantial form of the body.

Hi Shane.

Thank you for your input. A few comments by way of reply.

(1) My OED defines "proposition" as "a statement expressing a judgement or opinion". The last thing my "10 Propositions" are meant to be is apodictic - which is why I welcome your comments - nor exhaustive - which is why I would certainly not dispute your point about humans beings as rational (good Thomist that you are!). Further, that they are not as discursive as you would like - e.g. defining terms, arguing a case pro and contra, etc. - is, I'm afraid, the nature of the genre, particularly in this case where the propositions are even more lapidary and suggestive than usual.

(2) Regarding your physical/spiritual dichotomy, what Ben said. And a further methodological point: in good Barthian fashion, I would submit that theological discourse is not bound to proceed from the possible to the actual; in fact, just the reverse. At the eschatological extreme, the church proclaims the resurrection of the body, which Paul describes as a "spiritual body". It is possible because it is revealed as actual in the resurrection of Jesus. I can't explain it; heavens, I can't even imagine it!

(3) It is not, to me, "self-evidently false" that human beings have no being apart from others. Even your shipwrecked soul is in relationship to other people, fundamentally because he is relationship to Christ who is in relationship to other people, but also simply because as a linguistic being he is, ipso fact, a social being.

Thanks again for your incisive comments.

(1) A scientific discourse depends on arguments, not opinions. I have an opinion about the flat tax rate, but I don't really have any good arguments about it. I think this is permissible for me because I'm not an economist. It seems to me that theologians must also have some reasons for holding the opinions they do, but those reasons aren't always clear to us laypeople. We are like your 7th grade math teacher, we are happy if you get the right answer, but please remember to show your work so that we know you are getting the right answer for the right reasons, because you can persuade us only to the extent that we feel like you got the right answer for the right reasons. If the genre doesn't suit this kind of communication, perhaps a different genre would be more effective.

(2)(a) Ben is wrong on philological grounds. See my previous post.

(2)(b) The Achilles heel of Barth's maxim is that one man's modus ponens is another man's modus tollens: (I) Whatever is actual is necessarily possible; (II) It is impossible by definition that the physical (body) be non-physical (spirit), (III) Therefore, spirit is not body.

"But what about 1 Cor 15?"

Well, as the scholastics say, "When you encounter a contradiction, make a distinction." The distinction I make is between the different senses of the word 'spirit'. The sense I have been using in this debate I have defined in a precise technical way. In this sense "spirit" means the nonphysical part of the human person which animates the body and survives the body's death. This is the sense in which 'spirit' is 'non-physical'

1 Cor 15 clearly does not call the resurrected body 'spiritual' in this sense. Rather, in this passage the contrast is drawn between the celestial bodies (presumably the sun, moon and so forth, which contemporary Greek science asserted to be composed of a kind of incorruptible matter fundamentally different from the kind of matter found here on earth) and the corruptible terrestrial bodies we now possess. It seems to me that Saint Paul is saying that after the resurrection we will still be physical creatures, but our bodies will be composed of incorruptible matter similar to the heavenly bodies, because only this kind of body is capable of receiving immortality.

(3) I suppose you are a universalist then. If you took the view that there were people in hell I could point out the incongruity, but . . . At any rate, I don't find a formal flaw with this argument but it does seem very unpersuasive to me for some reason I haven't yet figured out. It is a bit like the objection to Bishop Berkeley, who believed that 'to be is to be perceived'. Someone objected to his theory that every time you blink the whole work goes out of existence, since you are no longer perceiving it. Berkeley's reply was that reality continued to exist insofar as it was continuously perceived by God. That solution seems to work formally, but it is hard to swallow. I have the feeling that the problem is deeper down somewhere. Am I really just a human in virtue of Christ's action. If God had decided not to become incarnate would no humans ever have existed? That would seem to be the implication of your view. Why is it our salvation and not our creation that makes us human? Perhaps your intuitions about this matter are simply radically different than mine are, but I maintain my previous opinion.

Post a Comment