“Philosophy, religion, science, they are all of them busy nailing things down, to get a stable equilibrium.... But the novel, no.... If you try to nail things down in the novel, either it kills the novel, or the novel gets up and walks away with the nail.” — D. H. Lawrence

My friend Kim Fabricius (who sometimes posts at Connexions) sent me this list of 15 essential novels for theologians, and he has allowed me to post it here.

1. Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter (1850)

2. Herman Melville, Moby Dick (1851)

3. George Eliot, Middlemarch (1872)

4. Leo Tolstoy, Anna Karenin (1876)

5. Fyodor Dostoevsky, The Brothers Karamazov (1880)

6. Franz Kafka, The Trial (1925)

7. Graham Greene, The Power and the Glory (1940)

8. Thomas Mann, Doctor Faustus (1947)

9. Albert Camus, The Plague (1947)

10. Ernest Hemingway, The Old Man and the Sea (1952)

11. J. R. R. Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings (1955)

12. William Golding, The Spire (1964)

13. Alexander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago (1975)

14. Umberto Eco, The Name of the Rose (1983)

15. Toni Morrison, Beloved (1987)

This is an excellent list, although I might have wanted to include Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones, James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Patrick White’s Riders in the Chariot, and Peter Carey’s Oscar and Lucinda, as well as anything by Charles Dickens and Jane Austen and Virginia Woolf. Oh, and something by John Updike and Salman Rushdie and A. S. Byatt.

Old Testament scholar

Old Testament scholar  Here’s our next “essential list,” kindly created by

Here’s our next “essential list,” kindly created by  Just hours ago, Benedict XVI released his much-anticipated first encyclical, entitled “Deus caritas est” (“God Is Love”). He describes the purpose of the encyclical in these words: “To experience love and in this way to cause the light of God to enter into the world—this is the invitation I would like to extend with the present Encyclical.” The first part of the encyclical speaks of the love of God, and the second part speaks of the Church’s call to love. You can read the full text of the encyclical in English

Just hours ago, Benedict XVI released his much-anticipated first encyclical, entitled “Deus caritas est” (“God Is Love”). He describes the purpose of the encyclical in these words: “To experience love and in this way to cause the light of God to enter into the world—this is the invitation I would like to extend with the present Encyclical.” The first part of the encyclical speaks of the love of God, and the second part speaks of the Church’s call to love. You can read the full text of the encyclical in English  I have recently discovered a beautifully-designed Catholic blog called

I have recently discovered a beautifully-designed Catholic blog called  Here’s our next essential list by

Here’s our next essential list by

The brilliant Roman Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar is best known for his vast theological trilogy, Herrlichkeit, Theodramatik and Theologik.

The brilliant Roman Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar is best known for his vast theological trilogy, Herrlichkeit, Theodramatik and Theologik. First, in his ecological/geographical study Jesus a Jewish Galilean, Sean Freyne argues that, while affirming the special place of Israel in God’s providence, Jesus nevertheless had a permeable understanding of Jewish identity and stoutly rejected the holy war ideology of the Hasmoneans. Freyne also suggests (a) that Jesus’ interest “was in the creator God rather than in the God of Sinai and the Exodus, and that his lifestyle was based more on the story of Abraham than on that of Moses”; and (b) that these emphases “are very much in line with Isaiah’s trajectory also and reflect the outlook which supports the servant’s mission and values.”

First, in his ecological/geographical study Jesus a Jewish Galilean, Sean Freyne argues that, while affirming the special place of Israel in God’s providence, Jesus nevertheless had a permeable understanding of Jewish identity and stoutly rejected the holy war ideology of the Hasmoneans. Freyne also suggests (a) that Jesus’ interest “was in the creator God rather than in the God of Sinai and the Exodus, and that his lifestyle was based more on the story of Abraham than on that of Moses”; and (b) that these emphases “are very much in line with Isaiah’s trajectory also and reflect the outlook which supports the servant’s mission and values.” “Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.” —Ludwig Wittgenstein

“Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.” —Ludwig Wittgenstein Here at Faith and Theology, our new blog of the week is Phil Harland’s

Here at Faith and Theology, our new blog of the week is Phil Harland’s  Yesterday I was in bed with a cold, and I decided to cheer myself a little by reading Gerd Lüdemann’s book The Resurrection of Jesus: History, Experience, Theology (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994). My three-year-old daughter came and asked me what I was reading, and I told her it was a book about Jesus rising from the dead. She was delighted to hear this, and she broke spontaneously into the following song (she is always inventing songs):

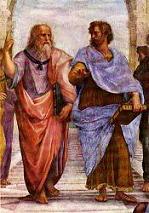

Yesterday I was in bed with a cold, and I decided to cheer myself a little by reading Gerd Lüdemann’s book The Resurrection of Jesus: History, Experience, Theology (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1994). My three-year-old daughter came and asked me what I was reading, and I told her it was a book about Jesus rising from the dead. She was delighted to hear this, and she broke spontaneously into the following song (she is always inventing songs): I invited Kim Fabricius to create a list of essential paintings for theologians. Kim has studied art and has spent time in many of the world’s great art museums, and he laboured long and hard to produce this list of 20 paintings. To make the list manageable, Kim imposed the following limits: Western art only (so no icons, no African or Asian art); paintings only (with one necessary exception); paintings “with a signature” (so no anonymous works such as manuscript illuminations); only one work per painter; and finally, Christ himself must be depicted in the painting.

I invited Kim Fabricius to create a list of essential paintings for theologians. Kim has studied art and has spent time in many of the world’s great art museums, and he laboured long and hard to produce this list of 20 paintings. To make the list manageable, Kim imposed the following limits: Western art only (so no icons, no African or Asian art); paintings only (with one necessary exception); paintings “with a signature” (so no anonymous works such as manuscript illuminations); only one work per painter; and finally, Christ himself must be depicted in the painting. The new issue of the

The new issue of the  Our local classical music aficionado,

Our local classical music aficionado,

In response to our recent “essential” lists, alternative lists have been posted at

In response to our recent “essential” lists, alternative lists have been posted at  The new blog of the week is Todd Vick’s

The new blog of the week is Todd Vick’s  T. F. Torrance is my favourite British theologian, and his work has influenced me deeply (especially his work on science, theological method, and the Trinity). Although I have read most of his books, I have never read his collection of sermons, When Christ Comes and Comes Again (London: Hodder, 1957).

T. F. Torrance is my favourite British theologian, and his work has influenced me deeply (especially his work on science, theological method, and the Trinity). Although I have read most of his books, I have never read his collection of sermons, When Christ Comes and Comes Again (London: Hodder, 1957).